Pakistan’s EMI story becomes legible when it is treated as a subset of the retail payments machine that the State Bank has been steadily expanding and instrumenting. In the most recent full-year snapshot, retail payments reached 9.1 billion transactions with a total value of PKR 612 trillion, and digital channels accounted for 88% of retail transactions. That is the headline shift: digitisation has stopped being a niche behaviour and become the dominant pathway for low-value retail payments, even as value still concentrates elsewhere. But the EMI question sits inside the composition of that digital share, not inside the headline itself. Digital growth in Pakistan has been driven by mobile and internet channels, branchless banking ecosystems, and instant rails that increase velocity. Velocity is not the same thing as stored value. That difference is precisely what has shaped the outcomes for EMIs since 2020.

The enabling infrastructure is large and uneven. Pakistan’s retail payments ecosystem is supported by a physical and agent network that remains enormous even as digital volumes rise: 18,049 bank branches, 18,655 ATMs, 120,641 POS terminals, and 648,333 branchless banking agents. That distribution system matters because it explains why money moves digitally but returns to cash so easily, and why balance retention inside wallets is structurally difficult. It also explains why a payments-only institution is exposed in a way a bank or telco wallet is not. A bank can use deposits to subsidise the cost of payments. A telco wallet can lean on distribution and adjacent revenues. An EMI has neither. It is regulated like a financial institution but monetised like a utility.

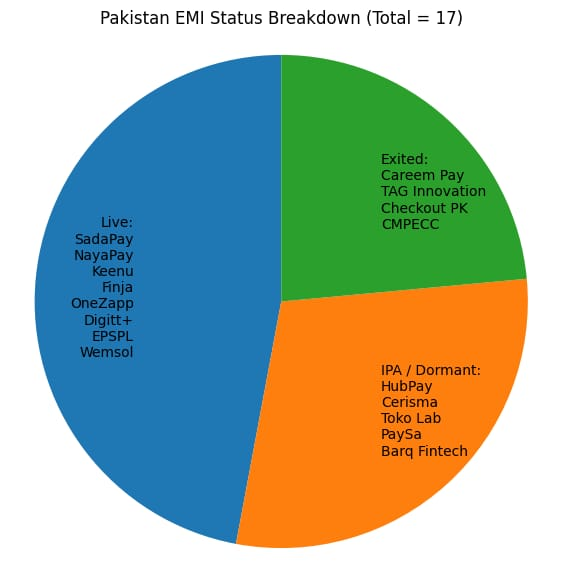

This is the context in which roughly sixteen identifiable entities entered the EMI corridor between 2019 and 2024: SadaPay, NayaPay, Keenu, Finja, OneZapp, Digitt+, HubPay, Cerisma, Toko Lab, PaySa, Barq Fintech, Careem Pay, TAG Innovation, Checkout Pakistan, CMPECC, and the wider cohort that appeared in the same regulatory orbit as approvals and withdrawals accumulated. In the early phase, in-principle approval flattened distinctions. It made these entrants look like a cohort. They were never a cohort. They were a funnel. A payments market can be growing rapidly and still be hostile to payments-only economics, especially when the growth is concentrated in low-value transfers that do not leave balances behind.

The compliance and pilot phase is where the first separations typically occur, and Pakistan’s data shows why. By Q2 FY24, SBP’s own reporting noted that digital transactions made up 82% of overall retail transactions during that quarter, up from 80% in the previous quarter. In other words, the machine was already running at scale. At the same time, SBP-linked reporting showed EMI registered e-wallets at 2.7 million in Q2 FY24 after a 15% quarterly increase, while branchless banking providers had around 67 million registered m-wallets. Those numbers alone explain the competitive terrain. EMIs are operating in a landscape where the mass market wallet base is already owned by branchless ecosystems and where the marginal cost of distribution is lower for incumbents than it is for new regulated payment entities. It also clarifies why several IPA-stage names can remain technically authorised but commercially muted: progress from approval to meaningful adoption is not simply a product question in Pakistan, it is a distribution and switching-cost question.

The launch phase is the most misleading milestone in an EMI’s life because it makes the story look binary live or dead when the more important distinction is live but fragile versus live with a defensible niche. SadaPay and NayaPay emerged as the most visible consumer-facing EMIs, with different approaches to recurring usage, while Keenu’s trajectory continued to point toward merchant infrastructure as the more stable equilibrium. Finja’s arc reinforced another common pattern: payments are a feature until they are forced to become a business. When that happens, the maths starts asserting itself. Even in a year when the national system is processing billions of retail transactions, the average EMI customer can remain low-balance and low-retention. Interchange remains capped. Float income remains marginal because balances are transient. The cost base does not care. Compliance and monitoring costs scale with activity and expectation, not with profitability.

Raast made this dynamic sharper, not softer. It upgraded Pakistan’s retail rails and increased transaction velocity in ways that benefit the system but complicate wallet stickiness. SBP reporting shows that since launch until June 2025, Raast processed a cumulative 1.9 billion transactions amounting to PKR 44.3 trillion. At the quarterly level, SBP’s own releases show Raast processing 140 million transactions worth PKR 3,437 billion in Q3 FY24, while another SBP quarterly release later reported 371 million transactions worth PKR 8.5 trillion in a single quarter, alongside cumulative totals crossing 1.5 billion transactions and PKR 34 trillion in value at that time. Those figures are not just impressive adoption numbers; they describe a system optimised for movement. Instant, interoperable transfers reduce the need for a consumer to keep money parked inside any single wallet. Raast increases throughput and lowers friction. It does not, by itself, create balance retention. For EMIs whose business model depends on volume plus some degree of stored value behaviour, a rail that accelerates exits can be a structural constraint even as it grows the overall pie.

The payments market also grew in the places that matter for narrative credibility. In FY24, SBP’s annual review noted 309 million e-commerce payments with a value of PKR 406 billion. That matters because it signals rising digital commerce flows, but it also shows the typical pattern: large counts, relatively modest value compared to the overall PKR 612 trillion retail payments figure reported in FY25. The value concentration remains elsewhere. Payments scale in Pakistan is real, but it is not uniformly monetisable. This is why the EMI cohort does not convert neatly from approvals to durable businesses, and why the “life cycle” of an EMI tends to feel like prolonged exposure to fixed costs rather than a clean path to profitability.

Exits, when they occurred, tracked this logic. Careem Pay’s withdrawal reflected a platform recalculating the cost of staying regulated for a payments business that could not be cross-subsidised indefinitely. Checkout’s retreat reflected global prioritisation in a market where transaction growth does not translate predictably into margin. TAG’s collapse was regulatory in form but economic in consequence: governance failure becomes fatal faster in a low-margin, high-compliance category. CMPECC’s disappearance, less loudly discussed, sits within the same attrition pattern. By the time you reach 2025, the pattern is not hard to describe: of roughly sixteen names that entered the corridor, only about six are meaningfully live, and only two or three appear positioned for durability without constant strategic reinvention.

What follows from the numbers is not a morality tale about innovation versus incumbency. It is a diagnosis of incentives. Pakistan’s retail payments engine is now massive by transaction volume, with digital rails carrying the majority of retail transactions, while a large physical and agent network keeps cash-out friction low. Raast has scaled into the billions of transactions and tens of trillions of rupees in cumulative value, accelerating velocity and interoperability. Branchless ecosystems have registered wallet bases in the tens of millions, shaping distribution and behavioural norms. In that environment, a standalone EMI survives not by being “the best wallet” in abstract terms, but by occupying the few zones where money pauses rather than passes through: cross-border receipts, merchant settlement loops, backend integrations, or recurring bill flows that produce predictable usage. That is why the survivals tend to look like adaptation, and why the future of EMIs increasingly looks like consolidation into larger systems rather than domination as consumer brands.

Source 1 | Source 2 | Source 3 | Source 4 | Source 5 | Source 6

Follow the PakBanker Whatsapp Channel for updated across Pakistan’s banking ecosystem.